|

|  |

|

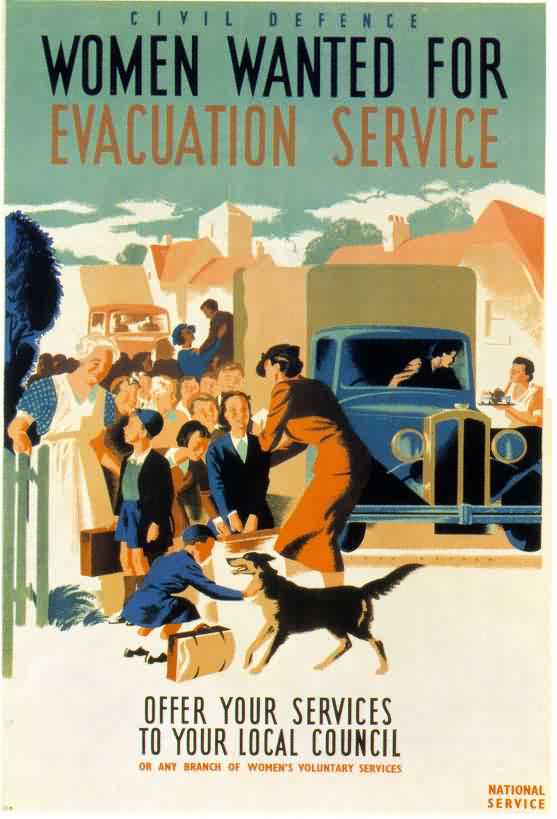

The influence for the Curtis Report came from success as much as from the depressing failures of past and existing legislation. The evacuation of children from the cities during the Second World War, proved for the most, an enlightening success. Instead of placing children and young people into institutions they were placed into, by in large, caring families that proved to be far superior environments in comparison to institutional care, and were conducive to a more normal socially acceptable upbringing.

|

| Wartime evacuation proved that boarding out worked. Click on picture |

As with previous wars, the second was no different in highlighting, to a wider nation, the detrimental effects that poverty and inner city life had on the working classes. Tragically, it seemed that the health of the urban working classes was only an issue when they were exposed as not being physically up to the job of laying down their lives for their country. In the case of the Second World War the urban exodus of children, showed, once again the vast polarity in the quality of health between rural and urban working classes. But in this instance, as opposed to other occasions when the same, nearly identical concerns were highlighted, the post-war government, and debatably even the opposition, in the long-held myth of consensus, were willing to enact robust, unique welfare institutions concerning the care for those that were unable or incapable to care for themselves. The recommendations laid out in the 1946 report stressed that evacuation had proved that boarding, wherever possible, should replace the traditional, large institutions. The recommendations of the Curtis Report were adopted and enforced by the 1948 Childrens Act.

Given the rather overwhelmingly philanthropic attitude of war-time and early post war Britain, the most unique and, perhaps so far the most far reaching piece of legislation governing the care of children and measures to protect them was passed largely unnoticed where as previously such legislation would have been strongly contested and opposed.

|

|

|

The report condemned many of the institutions, claiming that they stigmatised those who lived there, (yet the childrens officers, the pre-curser of the social worker, became equally stigmatising to those that required help, or feared their child being taken away due to the perceived lack of care they were financially able to provide). Most of all the report, felt that fostering was the ideal way for a child to be cared for when his/her parents/guardian were not able to do so. Efforts were to be concentrated on fostering rather than placing children in institutions, claiming that:

A vigorous effort to extend the boarding out system for children in the care of local authorities should in our view be made, so far as homes of a good standard in all respects can be found

But it realised that changing a century old system of childcare provision was not going to be easy. Despite all the evidence and widespread acknowledgement that many institutions were wholly unacceptable as providers of care, and that the success of war-time boarding out pointed to a drastic reorientation of the way children and young people should be treated and cared for, old habits and methods persisted. The report noted that:

It is rather surprising to find that of the 125,000 children coming within our first survey, only 31,000 are boarded out and 11,000 of those have been placed without the help of the local authority

Many previous methods of boarding out were condemned, particularly those that recalled the young person to the institution between the ages of 14-19, for supposed training. Training which was, in fact, just a cheap pair of hands to look after the disabled and infant children in the home. Also the report highlighted a long held and widely appreciated obscene tendency that was:

To assume that the child should not be placed in a better class of home than that of the home that it came from chilling really

The obvious hurdle for the newly placed emphasis on foster care was the provision of foster families themselves. Not only were homes sought above institutions, but new departments in each county, across the country were given the specific task of investigating and preventing abuse and neglect. As any social investigator has proved, when you go looking for hardship, you will find it. Neglect and abuse proved to be more widespread. Preventative, in house methods to keep the child in the home were not as successful as they were predicted and higher numbers than anticipated required third party, state intervention for their own protection.

Meanwhile many of the institutions upon recommendations, highlighted by the Curtis Report, had closed down, yet the level of foster care to take up the slack failed to materialise. The success of war-time boarding out did not transfer to peace. Although the government gave reasons for this, it could be cynically but accurately regarded that the fostering/boarding out was something that the wealthy, middle classes were only willing to do when national emergency, and the imminent threat of death from air raids was present. Caring for the children of the working classes, whose parents would not care for them themselves was perhaps viewed as not the same thing and did not encourage anything like similar numbers to step forward. The Curtis Report gave more charitable reasons, yet most became redundant within a few years of the war. Numbers of foster carers lagged seriously behind the numbers of those that required homes and that were left languishing in institutions that successive governments were loathed to support. Childrens homes remained stigmatised and under-funded albeit being the only option for many as fostering failed (and always has) to keep pace with demand.

|

|

|

|  |

|

Charitable objections to fostering laid out in the curtis report. Most were redundant in the in next few years, yet there was no significant increase in numbers willing to foster.

-

The weariness induced by war conditions which have made a number of very suitable foster parents who have housed evacuated children feel a strong a desire now that peace has returned to have their homes to themselves. We are informed that only a small proportion of billetors are recommended as foster parents, approved by the local authority, and willing to continue.

-

All this, while true in parts ignores a fundamental attitude that many people did not regard boarding out as a suitable method for looking after children whose parents were unwilling or unable to look after them themselves. It was OK when it was children per se, and there was the threat of German bombs, but the post-war abused and neglected children of the working classes, seemed to be for many, and quite sadly so, a different case.

|

| Look here young man, my philanthropy only extends for the duration of the hostilities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|  |